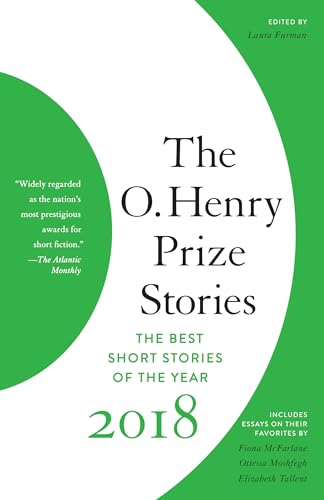

Items related to The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 (The O. Henry Prize...

"The Tomb of Wrestling," Jo Ann Beard, Tin House

"Counterblast," Marjorie Celona, The Southern Review

"Nayla," Youmna Chlala, Prairie Schooner

"Lucky Dragon," Viet Dinh, Ploughshares

"Stop ’n’ Go," Michael Parker, New England Review

"Past Perfect Continuous," Dounia Choukri, Chicago Quarterly Review

"Inversion of Marcia," Thomas Bolt, n+1

"Nights in Logar," Jamil Jan Kochai, A Public Space

"How We Eat," Mark Jude Poirier, Epoch

"Deaf and Blind," Lara Vapnyar, The New Yorker

"Why Were They Throwing Bricks?," Jenny Zhang, n+1

"An Amount of Discretion," Lauren Alwan, The Southern Review

"Queen Elizabeth," Brad Felver, One Story

"The Stamp Collector," Dave King, Fence

"More or Less Like a Man," Michael Powers, The Threepenny Review

"The Earth, Thy Great Exchequer, Ready Lies," Jo Lloyd, Zoetrope

"Up Here," Tristan Hughes, Ploughshares

"The Houses That Are Left Behind," Brenda Walker, The Kenyon Review

"We Keep Them Anyway," Stephanie A. Vega, The Threepenny Review

"Solstice," Anne Enright, The New Yorker

Prize Jury for 2018: Fiona McFarlane, Ottessa Moshfegh, Elizabeth Tallent

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The subject matter of the twenty stories in The O. Henry Prize Stories is so varied that even naming it feels reductive: a violent home invasion, an illiterate writer of letters from the dead, a retrospective homage to a failed marriage, an inconspicuous man in a very small town who bears witness to the great world’s horrors.

It becomes second nature for passionate readers to identify and consider the elements of fiction: plot, language, characters, setting. Subject matter seems like the most obvious one, yet is perhaps the least important in the long run. While an interesting subject might initially attract readers, it won’t keep them there unless the formal elements are in balance.

For the author, subject matter is more complicated. Each element of a story can seem to have its own notion of its importance, so that the writer often feels in control of nothing. Add to this the fact that a writer can start with one idea of what the story is about and end by realizing that it’s about something else entirely. Many authors say that they write to understand their own lives, so that even when a writer thinks she’s creating a unique, completely invented character, she isn’t surprised to recognize someone she knows lurking in the portrait—or even herself.

Nothing matters in the end except the story itself.

After you have completed a story in The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018, you might find you have two different answers to the questions “What is the subject matter?” and “What is the heart of the story?” And if you turn to “Writing The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018,” you can see what answers the authors themselves have to offer.

Jo Ann Beard’s “The Tomb of Wrestling” is spectacular in the fullest sense of the word: at once a spectacle and an impressive artistic achievement. Jurors Fiona McFarlane and Elizabeth Tallent chose “The Tomb of Wrestling” as their favorite story (pp. 347 and 350).

Here’s a story in which subject matter and plot march with locked arms. A woman is alone in her house. An intruder enters and attacks her. They fight. One wins and one loses. Beard describes their battle in raw and realistic detail. And yet, as in any short story, there’s a story underneath the story, and this understory is immediately hinted at by the second clause of the first sentence: “She struck her attacker in the head with a shovel, a small one that she normally kept in the trunk of her car for moving things off the highway.” Surely every reader wants to say, Who cares how big the shovel is or why she keeps it in her trunk? Get on with the fight. The first clause is so strong that the reader wants to know what happens next, which is one definition of plot.

But we care about the shovel at least in part because the story is also about the particulars of the antagonists. We learn their names and stories, what each of them cares about, and how they came to be in the house at the same moment. We also learn where their minds are wandering, through passages that step away from the physical struggle. The mind never stops wandering, not even when the body is fighting for survival. Beard catches perfectly each character’s strong will to live. By the story’s end, the reader is fascinated as much by their mental ramblings as by the specifics of the struggle, and in this way “The Tomb of Wrestling” resembles what we call real life.

Marjorie Celona’s “Counterblast,” chosen by 2018 juror Ottessa Moshfegh as her favorite story (p. 348), is funny, wry, sad, and full of energy. The narrator tells about the failure of her marriage and what she was like as the mother of an infant. The action centers on the death of her father-in-law and her interactions with her husband and his sister. The most intimate relationship is between mother and baby. While many mothers can anticipate their baby’s desire for food, a change of diaper, or sleep, our narrator is so attached that she feels little else but her yearning to be with her child. Adults make little sense to her; they’re annoying and their motivations impossible to discern. She’s set apart from her peers because of her desires, her unnamed and inchoate feelings that are the understory beneath the comedy of child care, in-laws, and her recurrent annoyance with her handsome husband, for whom life seems to be very easy. The last line of “Counterblast” is at first a puzzlement and then a revelation.

“Nayla” by Youmna Chlala begins with a place: “There was sun and then there was more sun and more sun. You can’t imagine loss when it’s sunny. . . . I was still in this camp in the desert, worming my way into acceptance while years—let’s count them . . . something like 365 × 6 + however many days—had gone by.” The word acceptance has two meanings here: acceptance into another country, which every refugee needs, and acceptance by another person, which every person desires.

At a party, the narrator meets Nayla, her cousin Marwan’s girlfriend, an ambiguous figure because she is a widow, and they become friends.

That summer, I practically lived in her apartment, a tiny place right above her late husband’s family’s house. I’d come over and we’d drink prosecco (pretending we were in Italy) and invent recipes together. We traded food for the bubbly wine with Ahmad, the liquor store manager. We made him fish fattoush; lamb-stuffed eggplant; pistachio, orange, and cardamom cookies; and vegetarian kibbeh with extra pine nuts.

Lucky Ahmad! Slowly the two young women come to trust each other, to share their losses and to confide what it is to be a survivor. The richness of their friendship in what is essentially a prison is perfectly conveyed by Chlala’s gifted prose.

“Lucky Dragon” by Viet Dinh also begins with the sun, though this is a sun that betokens devastation: “The second dawn rose in the east, at nine in the morning.” In the nonchalance of this first sentence, Dinh warns his reader that something is terribly wrong. The order of things is disturbed. The second dawn is no dawn at all but a nuclear explosion, a test by the Americans.

One member of the Lucky Dragon crew dies quickly and is buried at sea. The rest don’t merely sicken and die; they first suffer horribly, including the ship’s captain, Hiroshi, and his friend Yoshi. Some of the crew previously survived the Tokyo firebombings, others the battles in the Pacific. Hiroshi and Yoshi were together as soldiers in the Philippines and as prisoners of war. Together they transform into unrecognizable creatures as their skin scales and hardens. Dinh portrays not only their physical suffering but what their nation makes of them: first as victims, next heroes, finally as monsters. Their treatment makes a mockery of politics, nationalism, and military pride. In the end, Hiroshi and Yoshi have only death, the sea, and each other.

Michael Parker’s “Stop ’n’ Go” is a two-paragraph story whose emotional depth is masked by the banality of the main character. He is stoical, much attached to his habits, clothing, and schedules. His children have gone away. He no longer farms but still surveys his fields, now rented out to a company from out of state. We see his wife in her housecoat “wordlessly” making his customary breakfast. Nothing in the present quite makes sense to him. “Maybe I have outlived time,” he thinks.

So far, so good. Maybe the reader thinks that, aside from Parker’s elegant prose, this story about a grumpy old guy has nothing to reveal. Then, in the middle of the paragraph, everything changes. The old farmer’s world seemed entirely local, but the reader learns that it’s larger and more awful than it appears to be. With the words “In the war,” we’re taken back to his youth, back to war in another country, to being wounded, to a moment of unexpected desire, to seeing the worst that one human being can do to another, and then to seeing people whose ways are, to him, even more incomprehensible, more foreign and haunting.

Dounia Choukri’s “Past Perfect Continuous” is another meditation on war and memory but it’s also a disquisition on time, as the title indicates. Here are war, time, and memory—her family’s past and her present—considered by a young German woman. She comes from stolid women, “married to reasonable men with ice-blue eyes, men who only traveled in wartime.” Her family is bent on forgetting and denying their country’s (and their own) recent past. They yearn for the better days of a whitewashed past, whether embodied by Gene Kelly’s dancing or recollections of past winters, which “aren’t what they used to be!” The narrator, stranded in her adolescence, observes that “there’s a particular loneliness to sitting down at a table others have already eaten at, flicking at hard crumbs and tracing the rings of cleared glasses with your finger.” And then Aunt Gunhild, the narrator’s Nazi great-aunt, makes a visit, much to the family’s chagrin. She is “a smoker in a family in which women . . . didn’t smoke,” and a living ghost from the past, a living answer to the narrator’s question, “But what about the Second World War, huh?” The visit of her transgressive relative is inspiring to the narrator, an awkward thirteen-year-old, who’s unprepared for what the future seems to offer—“breasts, bras, boys.” In the atmosphere of her family’s nostalgia for a past that never existed, she tells the reader, “Part of me wished for a past without the need to fill in the present.”

Aunt Gunhild has lost the right to be nostalgic for her past. Through her visit, the narrator learns that time can be a false analgesic and that it’s hard to learn time’s lessons: “When the past sucks it just becomes a welcome lesson on how not to do things.” “Past Perfect Continuous” isn’t only a story about German history, it’s also a tracing of a young girl’s growth toward independence and a liberation as glorious and complicated as the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Thomas Bolt’s “Inversion of Marcia” is also narrated by a young girl. Mary’s on a family vacation with her parents; her older sister, Marcia; and the gorgeous and seductive Alicia, who is helping out “in exchange for a free trip to Italy.”

Not surprisingly, complications ensue. The parents withdraw into their own problems, reappearing periodically to drive the girls to Naples and other sights. A painful triangulation develops as Mary observes her sister’s increasingly sexual involvement with Alicia. Alicia’s wardrobe and makeup, the attitudes she strikes, the cigarettes she smokes, all seem perfect and perfectly annoying to our shrewd narrator. Mary knows that she’s about to lose childhood’s freedom to the questionable joys of adolescence. She watches Alicia and Marcia like a disapproving hawk, hovering and waiting to be included.

Thomas Bolt’s generous story is told with a bit of a novel’s discursiveness but he maintains the story’s tight focus on Mary’s quiet maturing and how she comes to understand something of the adult life she will soon undertake. She’s torn between copying Alicia’s ways and detesting them; between hating and loving her sister as Marcia moves through her first love affair; between thinking of her parents as distant monoliths and seeing their adult troubles as real and perhaps even forgivable.

Marwand, the Afghan-American narrator of Jamil Jan Kochai’s “Nights in Logar,” is on an expedition to find the fierce and unfriendly family dog, Budabash, who’s somehow gotten free. It’s a hot day and the mission is a welcome distraction but also dangerous, even in the current lull or temporary “coma” in the American war.

Marwand is in the company of Gul and Dawoud, his almost-peer uncles, and his cousin Zia; the boys range in age from twelve to fourteen. Unlike Marwand, who’s there on a visit from his home in America to his mother’s family village, Gul is wise in the ways of Logar and declares that only four of them can go looking for the dog. Marwand’s younger brother cannot be invited along. “ ‘More than four,’ he told me and Zia and Dawoud as we sat between the chicken coop and the kamoot, ‘and we’ll look like a mob, but any less and we might get jumped or robbed.’ ”

Part of the reader’s entertainment in Kochai’s lively story is the mix of American slang with Pakhto, a duality that highlights Marwand’s double existence. (On losing a bid to include his brother, here is his response: “ ‘Well, fuck,’ I muttered, in English, and relented to the will of the jirga.”) Marwand has two nationalities, two homes, two identities, and is at times comfortable with neither.

Even the missing dog is part of a duality. On first arriving, Marwand rushed to him, mistaking him for a favorite dog from years before. Budabash bites off the tip of Marwand’s finger, proving that he is not the Mr. Kareem of old, not an American dog to be “hugged and petted and neutered” but “a mutant,” perhaps like Marwand, neither one thing nor the other.

The four hunters see many things, and before long a numbered list of what Marwand sees reaches number twenty-one. They wend through graveyards and among slaughtered sheep, under mulberry trees and out in the open, over land possibly mined; they hunt until it is dark, darker than it ever is in the streets of Marwand’s America. Whatever America means to Marwand, with its safety and its grand promises for his future, it remains hard for him to measure it against Logar, where there’s a prayer and a story and an obligation to structure the days and nights, and the familiarity of his family village.

The life of Trent, the twelve-year-old narrator of “How We Eat” by Mark Jude Poirier, is in its way as dangerous as Marwand’s is in an Afghan village. Trent lives with his ten-year-old sister, Lizzie, and their mother, who insists they call her “Brenda” or “Bren.” She’s a self-righteous, crazy woman with a hair-trigger temper, who wins arguments with her children by shifting ground. She routinely blames them for her every trouble. Brenda has trained Trent and Lizzie to find money for her, and when they do, she buys a small quantity of fast food for them to share unequally.

Trent tries to take care of Lizzie, who is still innocent enough to disobey Brenda. His love for Lizzie and his attempts to care for her lead Trent into trouble with Brenda but also gain him a painful chance to escape.

In Lara Vapnyar’s funny and moving “Deaf and Blind,” the narrator views love, sex, and adult communication through the eyes of herself as a child.

Her mother’s dear friend Olga visits Moscow as often as she can. The two women met when they were both undergoing treatment for infertility, which worked for the narrator’s mother but not for Olga. Olga’s husband, whom she doesn’t love, remains crazy about her. The narrator’s father leaves her mother, marries again, and becomes possessed by a new baby, neglecting the narrator. The situation is static until Olga falls in love with Sasha, a deaf and blind philosopher, who becomes an object of fascination for the narrator. She’s learning about love in its eccentric and inconvenient possibilities, for, as her grandmother offers, “ ‘We don’t choose who we love.’ ”

Stacey, the narrator of Jenny Zhang’s “Why Were They Throwing Bricks?,” is having problems with a different kind of love. For Stacey, and then for her younger brother, being loved by their grandmother is like being the object of a boa constrictor’s affection. Their grandmother is used to getting her way and never gives up. Mixed with the story of Stacey’s distancing of herself from her grandmother and her Chinese identity as she grows up in America is the story of her grandmother’s own suffering. Unfortunately, that very real suffering doesn’t make her grandmother any easier to love, though it makes Stacey—and her story—more nuanced and complex. The story’s title evokes the grandm...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAnchor

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 0525436588

- ISBN 13 9780525436584

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages432

- EditorFurman Laura

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 (The O. Henry Prize Collection) [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780525436584

O. Henry Prize Stories 2018

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 32722622-n

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 (The O. Henry Prize Collection)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # mon0000210668

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 Format: Trade Paper

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9780525436584

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 26375756244

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 (The O. Henry Prize Collection)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0525436588

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 (The O. Henry Prize Collection)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0525436588

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Language: eng. Seller Inventory # 9780525436584

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. 400 pages. 8.00x5.25x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # zk0525436588

The O. Henry Prize Stories 2018 (The O. Henry Prize Collection)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0525436588