Items related to The Shadow King

Driven out of Holland by the plague, Balthasar makes his way first to the raffish, cynical world of Restoration London and then to Barbados, a colonial society marked by slavery and savage racism. Every stage of his life is informed by the political and religious background of the era, and the rich, everyday human past, too, is brought vividly to life, in people's habits of thought and speech, their food and fashions, their medical practices.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The mechanisms of our bodies are composed of strings, threads, beams,

levers, cloth, flowing fluids, cisterns, ducts, filters, sieves, and other similar

mechanisms. Through studying these parts with the help of Anatomy,

Philosophy and Mechanics, man has discovered their structure and

function . . . With this and the help of discourse, he apprehends the way

nature acts and he lays the foundation of Physiology, Pathology, and

eventually the art of Medicine.

Marcello Malpighi, De Polypo Cordis (1666)

February 1662

"And now we come to the heart of the mystery, gentlemen. Come forward a

little, it is a sight you will seldom have an opportunity to see." Delicately he

traced the swollen, ripening curve with his forceps, as they all obediently

craned their necks. "About three months gravid, I should say. She should

have pleaded her belly, poor wretch. But perhaps she did not know the signs."

Putting down the forceps which he had been using as a pointer

since laying aside the mass of the intestines, he picked up a scalpel, and

began to cut. The thin, cold winter sun lanced down on the table, which was

positioned to catch the best possible light. The room was completely silent,

except for the precise, tearing sound of the blade sawing through tough

muscle.

Balthasar leaned forward with the others, sweating with sickly

fascination, breathing shallowly through his mouth. The meaty stink exhaling

from the opened body was an almost solid thing, though the girl had been

dead only forty-eight hours. Even though he was avoiding breathing through

his nose, it seemed to have coated his whole mouth and throat with a layer of

impalpable foulness. Incense burned in the room, but the delicate, musky

sweetness only intensified the horror of the stench.

The sight before him was profoundly disturbing for a young man

who had never before in his life seen a naked woman. The neck was of

course damaged by the garotte, but since they were clustered about the

lower part of the cadaver and the head was turned away from them it was not

visible; he could only see the line of the cheekbone. The upper part of her

body was pretty. She was very slight, bluish-white and waxen in death, with

pale, maidenly nubbins of breasts that suggested extreme youth; if he had

met her, perhaps carrying a pile of linen or a basket of eggs, he would have

flirted with her, sought a glimpse of those little breasts now so pitilessly bare

to his gaze. Yet the moment his eye strayed below the waist, he could no

longer even think of the body as human, it was something worse than

butcher"s meat. The abdomen gaped open, omentum and bowels laid to one

side to display the womb, like a terrible red egg in the nest of the pelvis. Both

legs had been sawn away just below the point where they met the torso. The

ends were dry and shiny like mahogany, with gleaming rings of paler fat and

ivory bone, and between the great dark-red meaty ovals, her shameful parts

were obscenely exposed in all their meagreness, adorned with a little tuft of

blonde hair. He kept looking at her sex and away again, revolted and excited,

and knew that his fellow students were doing the same. It was impossible for

him to associate the dry and abject tags of flesh that he could see with what

he had touched in his occasional fumblings beneath the skirts of whores,

which had seemed, at the time, a slippery pit fit to swallow the world. Is this

how all women are made? he wondered sickly, but was distracted from this

train of thought by Professor van Horne.

Pinning back the two halves of the womb, now completely

sectioned, he reached into it with the forceps, and brought forth a pale

homunculus attached to a long, bluish cord. "A male, I believe," he

announced, squinting at the tiny object expertly. "Well, perhaps the law has

spared him much suffering. He would not have amounted to much, with such

a beginning." Carefully, he laid the fetus down on a piece of white

linen. "Observe him well, gentlemen, so that his existence will not be

absolutely in vain. The head is well developed, though the eyes are not open,

and the heart is formed, as are the spine and the liver. We now know that his

heart would already have been beating, and it may be that this little creature

lived for some time after his mother met her end. He was not independent, as

the cord which tethers him to the matrix bears witness, but neither was he

wholly part of this wretched girl, any more than he was party to her sins. For

all we know, he was already dreaming when death came quietly into his

small world. So do we all begin."

Turning to the anatomical atlas which lay open on a lectern beside

the table, Professor van Horne began an exposition on the anatomy of the

uterus. Balthasar and his fellow students took notes conscientiously; he was

perhaps not the only one so disturbed by what he saw that he wrote

mechanically and followed little of what the professor said.

At last, the lesson came to an end. Professor van Horne threw a

sheet over the ruin of the girl and her child, while the students pocketed their

notebooks and prepared to leave. Feet clattering, they trooped up the wooden

stairs of the anatomy theatre, a precipitous, funnel-like oval of benches

designed to give students the best possible view of the dissection table at its

centre. Around the outermost set of seats articulated skeletons were placed,

a horse and its rider, a cow; their delicate white bones arrested by an

armature of wires and struts in postures which imitated their natural

movements in life. There were also human skeletons carrying banners, the

gonfaliere of Death: "pulvis et umbra sumus", "nosce teipsum", "memento

mori".

"D"you know who she was?" Balthasar asked his friends as they

emerged, shivering a little, into the raw air of February, hands deep in their

pockets.

"I"ve no idea," said Jan. "Willem, you went to the execution, didn"t

you? Did anyone say?"

"Yes. Well, what she was, anyway. She was a country girl, she

came to the city for work, and didn"t find it. She scrounged and starved for a

bit, maybe earned the odd stuiver on her back, the landlady got tired of

waiting and tried to take her clothes. They had a fight, she pushed the old

woman down the stairs and broke her neck, and the other lodgers caught her

before she got to the end of the street. Lucky for us, really. It"s my tenth

dissection, and only the first woman. It"s wonderful she was pregnant, I never

thought I"d get to see that."

"Luck indeed," said Jan, with passion. "Van Horne was right,

calling it a miracle. It was beautiful. I"ve wanted to see inside a womb for a

long time. He should"ve thrown the book away, sows and bitches are no

guide at all. Hardly anything he told us was supported by what we saw. I was

nearer than you, and I could see there wasn"t the slightest trace of two

chambers. The standard account needs complete revision, based on

observation alone."

"Was she pretty?" asked Balthasar suddenly.

The others looked at him, surprised. "Who?" said Willem. "Oh,

yes. Pretty enough. Pale as a cheese, but she was on the gallows, wasn"t

she? She might"ve looked all right, smiling. It was just an ordinary face."

Balthasar swallowed. Jan was incandescent with technical

enthusiasm, but he could not help thinking of the girl. His mind was bumping

around the unpalatable effort of imagining what it could be like to be so poor

that one could die in defending two or three guilders" worth of old clothes. At

the same time, he was uncomfortably aware that if his own ventures failed,

there was nothing to keep him from such an end. The thought of her stirred in

the pit of his stomach, and filled him with a strange nervous excitement.

Jan shook himself, as if shaking off a thought. "Let"s go for a

borrel, jonges. That was wonderful, but I want to get the stink out of my

throat. Anyone got a clove or anything?"

Balthasar had a paper of aniseed comfits, and passed them

round. Chewing their sweets, the three students headed for a nearby inn, "t

Zwarte Zwaan, their usual place of resort. It was not much of a place, but it

was fairly cheap, and the landlord kept a good fire and the news.

"Oh, good," said Balthasar as they pushed open the door, "this

week"s Courant. I"d better take a look. I want to see if Thibault"s been up to

anything, back home."

"You"ve had a lot of trouble down in Zeeland this last year,"

observed Jan sympathetically. "It"s a long way away, when there"s property to

think about. Have you got family down there – maybe your mother"s people?"

"No," said Balthasar hastily. "I"ve got no relatives. There"s just a

couple of old servants."

"Tough luck, Blackie. Something more to worry about. What"re

you drinking?"

"Brantwijn, please." They sat down together, Balthasar taking the

seat nearest the window, the better to see the dirty, poorly printed pages. All

three immediately began filling their pipes, and Willem began to tell Jan one

of his long, rambling dirty stories, leaving Balthasar in peace to scan the

paper. While his fingers filled and tamped the pipe with automatic skill, his

eye, running down the columns, was alert for a few specific

words, "Middelburg", "Zeeland", "Thibault". Thus, when his gaze passed over

the words "konigin van Bohemen", he did not at first register them; only a

strange double-thump of his heart. He looked again, and this time, saw what

was said. "The queen of Bohemia is dead in London." A strange, cold

sensation began in his stomach and diffused through his body. His mother

was dead, and he was completely numb.

"So, what d"you think of that, then, Blackie?" Willem"s voice broke

into his paralysis.

"Sorry?"

"You didn"t hear a word, did you? Is there trouble at home? You"re

a funny colour – you look as if you"d have gone pale, if you could."

"Oh, it"s nothing." Balthasar forced a smile. "I"m tired, I think, I was

working late last night." He put the pipe down unlit, reached for his brandy,

and gulped half of it in one swig. "God. This is terrible stuff. What d"you think

he puts in it?" As he had hoped, that turned the conversation.

Later, walking alone to his lodgings, he wondered what to do. The

obvious answer was to stay where he was and get on with his degree, but he

had an appallingly strong impulse to run for home which he knew to be futile:

his father, the only person he could possibly have talked to, had been dead

for five years. But he had brought none of his mother"s letters with him, since

he did not care to risk them outside the house, and he wanted very much to

reread them.

Once he was in the privacy of his own room and his mind was

working once more, he realised there was one thing he could usefully do, and

that was to write to Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, who, since his father"s

death, had been his only link with his mother. The old German had been a

court painter in England under both James I and Charles I, but had fled in the

early years of the Civil War, when Balthasar himself had been only a baby,

and settled in Middelburg. Pelagius, Balthasar"s father, always interested in

English exiles, had become acquainted with him, and had secured him

Elizabeth"s patronage. The portrait he had painted of her, which Pelagius

displayed in their small house in Middelburg, had launched him on a second,

modestly successful, career among Zeeland burghers and their wives, and

Jonson had been duly grateful.

It was Jonson"s image of a strong-featured, middle-aged woman

with hazel eyes, fabulous pearls and a low-cut dress, holding a white rose,

which was, to Balthasar, practically all that he knew by the name of mother.

When she had come to Middelburg for a week of sittings, he had been only

six, and he had not known anything of their relationship; try as he would, he

could remember nothing she had said to him, and his memory of how she

had looked was overlaid by the portrait itself. All he was sure of was the

lustrous, rustling folds of her silken skirts, and the scent of amber and orris

which they gave off; she had been exotic and awe-inspiring. His only real link

with her was the letters, which had begun only after his father had told him

who he was.

Due to the extreme secrecy of his birth and bringing-up, a

discretion that his father had imposed upon him so strongly that it felt like a

physical lock upon his tongue, when she wrote to him, as she occasionally

did after Pelagius"s death, the letters were sent under cover of notes to Mr

Jonson, and his replies, brief as they were, went the same way. In the course

of writing his letter to Jonson, he made up his mind. He would stay where he

was; he had neither money nor time to spare.

September 1663

The packet-boat Dordrecht was making its way up the with the sun lying low

on the horizon and making them all squint as they looked towards their first

sight of the town. Balthasar, at last, was going home. Chilled from the long,

cold journey threading through the islands of Zeeland, and uncertain in his

mind, he looked from Walcheren Canal towards Middelburg on the last leg of

its journey, up as the familiar defences of the Oostpoort came into view. He

longed for home, and yet the thought of it appalled him. In the depths of the

hold, roped and corded, were all his books and clothes from Leiden, together

with his certificates of graduation as a doctor of medicine. His life as a

student was now a thing of the past, before him was a house, and the two

servants who had brought him up, Narcissus and Anna. All the security he

had ever known. He longed to see them, and memories crowded in his head,

Anna"s warm lap, riding on Narcissus"s shoulders, the alarms and

excitements of childhood, how strong, wise and potent they had once

seemed to him, especially Narcissus. Now, their dependence terrified him.

He must succeed as a doctor to keep food in their mouths, coal in the cellar,

linen in the press. The death of his mother, so far away, had removed his last

point of resort beyond his own abilities, and she had left him nothing. The

servants were his to command, but also his to care for, and he was infuriated

by the assumption of helplessness in their confiding, painfully written letters.

If he failed, he thought grimly, they would all three beg on the streets.

Narcissus and Anna could, and would, do nothing to help him, or themselves.

The thought stayed with him through the protracted business of

tying up at the Oostpunt, hiring a handcart and porter for his luggage, and the

short walk home down the Spanjardstraat. When he came within sight of the

small, rosy-brick house called De Derde Koninck, the sound of the porter"s

cart rattling on the cobbles alerted the household, and Narcissus looked out.

In the slanting evening light, the round, dark head peering round the jamb of

the door seemed strangely creased and distorted; the familiar keloid scars of

ancient burns on Narcissus"s cheek and neck, traces of an accident which

had happened long before Balthasar was even born, seemed to pull his face

into grotesque lopsidedness; for a moment, he looked like a monster. The

next second, he recognised his master, and his face split in a wide...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0618149139

- ISBN 13 9780618149131

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages303

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

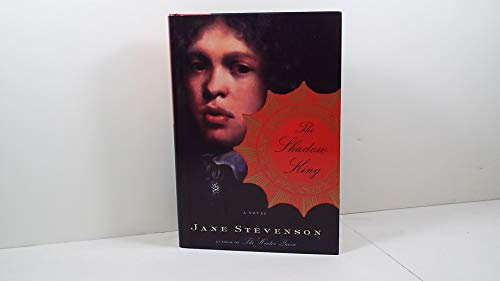

The Shadow King ; 9780618149131 ; 0618149139

Book Description Condition: New. Limited Copies Available - New Condition - Never Used - DOES NOT INCLUDE ANY CDs OR ACCESS CODES IF APPLICABLE. Seller Inventory # 0618149139N

The Shadow King (First Edition)

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. NEW YORK: Houghton Mifflin (2003). First edition, first printing (with full number line down to the 1). Hardbound. Brand new. Very fine in a very fine dust jacket. A tight, clean copy, new and unread. Comes with archival-quality mylar dust jacket protector. NOT price clipped. Shipped in well padded box. Seller Inventory # Stacks-Fiction-S5

THE SHADOW KING

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.03. Seller Inventory # Q-0618149139